***This is the first of two articles on the Opioid Crisis in the U.S. This article details the history, discovery, and early use of opioids. The second article will elaborate on the responsibility of scientists and physicians for enabling the opioid crisis in the U.S, as well as their current roles in eliminating it.

The number of opioid deaths in the U.S. has more than quadrupled since 1999. In a recent survey, 28% of U.S citizens believe the opioid crisis is a national emergency, and an additional 53% believe it’s a major problem but not quite an emergency [1]. Although the opioid crisis has recently gained headlines, the story of how opioid abuse infiltrated every state in the U.S has a deep-rooted history.

Where did opioids come from?

Most plants are built the same way. Roots anchor the stalk of the plant into soil, where it can absorb water and nutrients to help it survive. Above ground, leaves stuffed full of green chloroplasts soak up the sun’s rays and turn it into energy that the plant can use to grow.

The poppy plant, however, is unique. It harbors the most addictive compound known to humankind—opium, the natural precursor to every opioid that haunts addicted individuals, affected families and communities, and hospital emergency rooms everywhere. The origins of the poppy plant predate the ancient Egyptians, who first produced opium as a drug.

Not until the nineteenth century did opiates begin to turn their recreational drug use into a death sentence. Morphine, which is about 360 times stronger than Tylenol, was produced in 1803 and was used instantly in everything from cough syrup to pain relief on the battlefield. In 1853, Dr. Alexander Wood invented the hypodermic needle, providing a more effective delivery route of morphine, and later heroin, into the bloodstream. Opiates and the hypodermic needle quickly entered a marriage that has withstood the tests of time. Dr. Wood’s marriage, however, wasn’t as lucky. His wife became the first recorded overdose death from an injected opiate.

Moreover, heroin, five times stronger than morphine, was mass-produced (as non-addictive) in Germany by pharmaceutical giant, Bayer, in 1898. Fentanyl and carfentanil, 100 times and 10,000 times stronger than morphine, respectively, were first produced in the mid 1900s by Janssen Pharmaceutica.

How did opioids become so widespread in the U.S?

Opioid abuse precipitated across the U.S via a perfect storm of corporate greed, medical negligence, and ingenious drug trafficking.

While scientists pursued the “holy grail,” a non-addictive painkiller with efficacy that paralleled opiates, and the medical community remained uncertain about the addictiveness of opiates, Arthur Sackler spearheaded the marketing campaign that opened the floodgates for opioid use in the U.S. In 1951, he revolutionized drug advertising by sending sales representatives to physicians’ offices, where they bribed physicians to use their products and misled them about side effects and addiction.

Sackler’s grassroots advertising method was later used to convince physicians that prescribing opioids wasn’t just safe but also satisfied physicians’ moral duty to helping patients. (For Stephen Colbert’s summary of Sackler’s impact on opioid abuse, click here).

As Sackler sweet-talked doctors into using opioids, two events occurred that would permanently change the way opioids were viewed and used in the U.S.

Porter and Jick and the Xalisco Boys

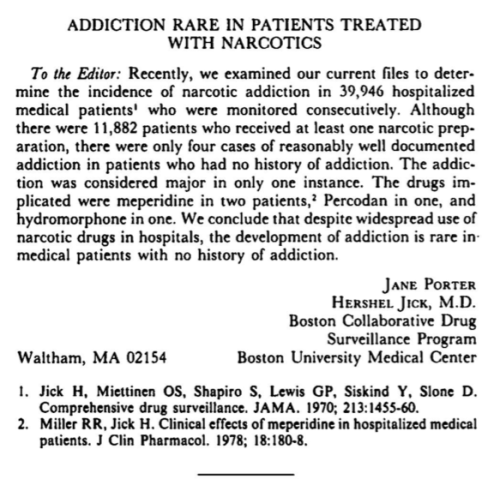

In 1980, Dr. Hershel Jick and a graduate student named Jane Porter penned the most infamous medical letter (below) ever published in the world’s foremost academic journal, The New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM). The letter is known most commonly as Porter and Jick.

After publication of Porter and Jick, doctors began prescribing opioids for all kinds of pain relief, even before administration of more commonly used drugs such as Tylenol. Experiencing back pain? Here’s an opioid. Have a toothache? Here’s an opioid. Dr. Jick, Ms. Porter, and doctors throughout the U.S stunningly failed to critique the most glaring shortcomings of the study—patients received narcotics on an in-patient basis, often times only a few administrations of the drugs. That’s hardly sufficient to develop an addiction.

Notwithstanding the glaring pitfalls of Porter and Jick, doctors across the U.S embarked on a crusade to end pain by prescribing narcotics to their patients. Little did they know, organized medicine would be responsible for the worst man-made epidemic ever.

While Ms. Porter and Dr. Jick were penning their letter that would ease the mind of every doctor who prescribed narcotics, a few opportunistic entrepreneurial families from Xalisco, Mexico started smuggling black tar heroin into the States. The Xalisco Boys, as Sam Quinones, author of Dreamland: The True Tale of Americas Opiate Epidemic, calls them, started to build a heroin empire in the San Fernando Valley of Los Angeles, California and would quickly spread their business from sea to shining sea.

Black tar heroin is unrefined heroin that, because of its crude processing methods, is cheaper to produce and even more potent than refined heroin. Because of its potency, heroin moguls could smuggle small amounts into the States that could be divided into even smaller quantities to be transported across the U.S and sold for an incredibly large profit.

Smugglers established heroin cells, or headquarters, in Los Angeles, then migrated to: large cities like Portland, Oregon; Memphis, Tennessee; and Honolulu, Hawaii, before moving into rural areas like Portsmouth, Ohio; Huntington, West Virginia; and parts of Alaska.

Distribution of black tar heroin was as sophisticated as any delivery service in the U.S. In fact, it would rival the efficiency of Amazon in terms of logistics; each cell had a fleet of drivers who would transport black tar heroin in tiny balloons stuffed in their mouths. Drivers would deliver addicts’ heroin to a pick-up location or to their homes and spit out a few balloons for the addicts to open and get their fix.

Then, the same process occurred the following day and every day after that—like room service. Addicts then told other addicts about the black tar heroin that gave them a better high at a fraction of a price. Soon, entire communities were addicted.

Why didn’t police catch on to this exchange of heroin? Police did. Except when they caught a driver, the driver simply swallowed the balloons, which erased any evidence of smuggling heroin. If they were caught red-handed, they were deported, and the cell would simply aid another young man in crossing the border and provide him a job as a driver.

The demand for black tar heroin skyrocketed after Porter and Jick led physicians to prescribe narcotics for every type of pain. Patients quickly became addicted to opiates but couldn’t afford to keep going to the doctor and paying for prescriptions. However, heroin delivered to your doorstep for the cost of a few pizzas was feasible.

Meanwhile, the biomedical (scientific + medical) community, who is mostly responsible for protecting societies from ravaging disease and preventable deaths, remained oblivious to the effect of their blind endorsement of narcotics, as well as the spread of heroin operations across the U.S. In fact, in 1996 Arthur Sackler’s pharmaceutical company, Purdue Pharma, developed OxyContin, which quickly became one of the most prescribed painkillers in the U.S. As a result, 80% of heroin addicts received their first fix from OxyContin (mostly) or another high-powered painkiller [2].

OxyContin was marketed as a time-released, non-addictive opiate for chronic pain patients. In 2007, Purdue Pharma was fined $634 million for false branding of OxyContin. Purdue was forced to reform OxyContin with abuse deterrents. As OxyContin’s true effects were revealed, physicians prescribed less of it. Addicts turned to the now well-established black tar heroin cells across the U.S to get their fix, and what we now know as the opioid crisis swept across the U.S like a raging California wildfire.

Not until the late 2000s did the biomedical community begin to appreciate the interconnectedness of false branding and overprescription of opioids, as well as concurrent widespread networks of heroin cells, and their causation of today’s opioid crisis.

Opioid use is not a modern-day phenomena. Opioid abuse and overdose, however, is. Today’s opioid crisis is a public health epidemic that arose from a combination of pharmaceutical malpractice, lack of scientific rigor and medical awareness, and infiltration of communities by black tar heroin.