*This is the second of two articles on the Opioid Crisis in the U.S. To read the first, click here.

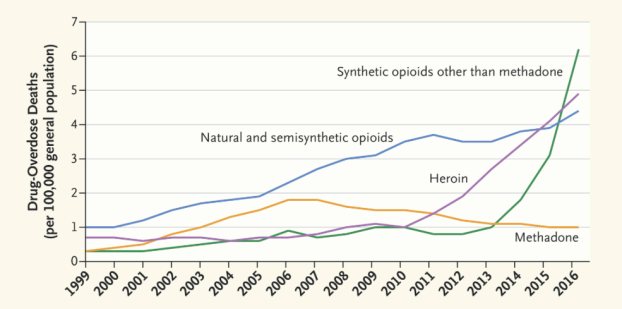

In 2016, over 64,000 people died from drug-related overdoses, more than all U.S deaths from the Vietnam War. The primary culprit—opioids.

Indeed, more than 90 Americans die per day due to opioid overdoses. Scientists and physicians can’t seem to stop the bleeding. In fact, opioid overdoses are still ballooning out of control, despite public health efforts to make opioid use safer.

As I previously discussed, the biomedical community harbors significant responsibility for enabling, if not encouraging, the use of opioids in the U.S. In short, a one-paragraph letter published in The New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM) stated that opioid use led to addiction in less than 1% of patients admitted to hospitals. The letter’s conclusions were technically correct.

Except, glaring limitations of the “study” were ignored, and the letter, now referred to as “Porter and Jick,” was falsely cited as proof that prescribing opioids for any and all pain was the right thing for physicians to do.

A recent study published in NEJM found that Porter and Jick has been cited 608 times, 439 (72.2%) of which cited it as definitive proof that opioids were not addictive. This led physicians to overprescribe opioids which subsequently increased addiction. This, combined with false marketing of OxyContin by Purdue Pharma, as well as the establishment of heroin cells by a few opportunistic families from Nayarit, Mexico, created the opioid epidemic in the U.S.

Although the biomedical community’s errors with Porter and Jick enabled the opioid crisis to take off, it is not too late for scientists and physicians to reverse the current exponential course of opioid deaths in the U.S. So, what can we do?

First, minimize the current detriment that opioid use has on users and addicts. Prioritize safe injection clinics instead of detoxification programs. Safe injection clinics provide clean needles for addicts, which prevents the spread of diseases such as Hepatitis C and Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV). Detoxification programs without continued follow-up care have proven ineffective.

Additionally, create anonymous drug testing facilities for addicts to test street drugs for dangerous additives such as ecstasy, fentanyl, and carfentanil.

Second, administer opioids such as buprenorphine that contain anti-overdose medication. Buprenorphine is similarly effective as morphine, but it contains naloxone (Narcan), the reversal drug for opioid overdoses. Efforts to administer buprenorphine as a safer opioid have been stymied due to a nationwide shortage of the drug.

Third, and most importantly, educate physicians on best practices for administering opioids and caring for opioid addicts. Two recent articles in NEJM demonstrate inconsistencies in administration of opioids, as well as lack of confidence in treating opioid addicts. Both studies suggest avoidable instances of death and patients becoming addicted to opioids.

More primary care physicians are refusing to prescribe opioids, citing fear of facilitating overdose of their patients. This, however, often leads addicts to acquire opioids on the street, and it neglects those in need of extreme pain relief. While taking opioids opens the risk of becoming addicted, the reality is that they are the most effective painkillers in physicians’ arsenals.

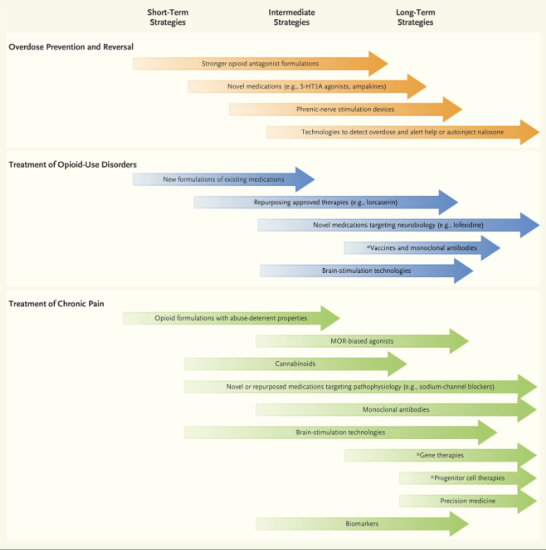

There is also more we can do from the research standpoint. Dr. Francis Collins, director of the National Institutes of Health, and Dr. Nora Volkow, director of the National Institute of Drug Abuse recently outlined several initiatives that the NIH and NIDA are spearheading.

In particular, the NIH and NIDA are supporting research attempts to develop less addictive yet equally effective painkillers. This is an extremely tall task.

Although, a recent study published in Nature suggests that opioids act on their receptor via two different signaling pathways, one that relieves pain and another that stimulates the reward pathway that leads to addiction. Development of a drug that stimulates only the pain relief pathway and not the reward pathway would achieve the long sought-after goal of a non addictive, opioid strength painkiller.

Meanwhile, other alternatives are worth pursuing. Scientists know the gene that is responsible for pain sensation. Forcing the body to express less of this gene may result in less pain sensation. Moreover, tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), a non-high-inducing component of marijuana, is a promising painkiller, but it is unlikely to receive significant research funding due to the stigma that hovers over marijuana use in the U.S.

While we wait for nonaddictive painkillers to be developed, more readily implementable strategies for combatting the opioid epidemic include: wearable technologies that monitor physiological signs of overdose and signal for help/inject Narcan when someone is in danger of overdosing; vaccines that target synthetic opioids (fentanyl and carfentanil); and making Narcan available over-the-counter at pharmacies.

The biomedical community is partially responsible for causing the opioid epidemic. It is even more responsible for ending the epidemic through: ensuring safe injection of drugs that lack dangerous additives, educating physicians on best practices for caring with opioid users and addicts, pursuing discovery of safer, more effective painkillers, and creating technologies that will monitor people for, and attempt to rescue them from, opioid overdoses.